I would like to spend the next few posts talking about a problem I read about in chapter 5 of the book Einstein Manifolds by Arthur Besse (it turns out that the name Arthur Besse is made up as you can read in the preface of the book). The question that we want to address is the following

Given a compact smooth manifold without boundary  , when is it possible to find a Riemannian metric

, when is it possible to find a Riemannian metric  in

in  satisfying

satisfying  for a given Ricci candidate

for a given Ricci candidate  ?

?

It is of course too ambitious to try to answer this question in full generality but we can start by showing some examples of Ricci candidates for which this equation does not have a solution.

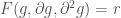

Trying to solve  for

for  amounts to solving a second order, quasilinear PDE on

amounts to solving a second order, quasilinear PDE on  , however, the main difficulty here is that the operator

, however, the main difficulty here is that the operator  is not elliptic.

is not elliptic.

A motivation for considering this problem comes from the question of existence of metrics with constant sectional curvature on  – manifolds (compact and without boundary). This of course has to do with the celebrated theorem of Richard Hamilton on the description of

– manifolds (compact and without boundary). This of course has to do with the celebrated theorem of Richard Hamilton on the description of  – manifolds with positive Ricci curvature:

– manifolds with positive Ricci curvature:

Theorem (Hamilton, 1982): Let  be a connected, compact smooth

be a connected, compact smooth  dimensional manifold without boundary and suppose that

dimensional manifold without boundary and suppose that  admits a metric

admits a metric  such that

such that  is positive definite everywhere. Then

is positive definite everywhere. Then  also admits a metric with constant sectional curvature.

also admits a metric with constant sectional curvature.

We will discuss some of the ideas involved in the proof of this theorem in future posts. A consequence of this result is that  is diffeomorphic to the quotient of the

is diffeomorphic to the quotient of the  -sphere

-sphere  by a discrete group

by a discrete group  .

.

Back to our original problem, recall that given a Riemannian metric  , the full curvature tensor is defined by

, the full curvature tensor is defined by

Where

![R(X,Y)Z=\nabla_{X}\nabla_{Y}Z-\nabla_{Y}\nabla_{X}Z-\nabla_{[X,Y]}Z](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=R%28X%2CY%29Z%3D%5Cnabla_%7BX%7D%5Cnabla_%7BY%7DZ-%5Cnabla_%7BY%7D%5Cnabla_%7BX%7DZ-%5Cnabla_%7B%5BX%2CY%5D%7DZ&bg=ffffff&fg=444444&s=0&c=20201002)

Here  is the Levi-Civita connection of

is the Levi-Civita connection of  .

.

The Ricci tensor is then defined as

.

.

Here are two basic properties of  :

:

1)  is symmetric in

is symmetric in  and

and  , i.e.

, i.e.

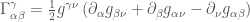

2) In local coordinates  looks as follows

looks as follows

We are using the summation convention (i.e we sum over repeated indices). The Christoffel symbols  are defined by

are defined by

Where  are entries of the matrix

are entries of the matrix  . This says that in local coordinates we can write schematically

. This says that in local coordinates we can write schematically  where

where  is a

is a  function that depends linearly on the entries of

function that depends linearly on the entries of  . If we then want to solve

. If we then want to solve  locally, property 2) tells us that we have to look at a system of the form

locally, property 2) tells us that we have to look at a system of the form

Property 1) tells us that an admissible Ricci candidate  has to be symmetric.

has to be symmetric.

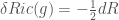

One encounters obstructions for solving this system right away. One of the main difficulties has to do with the fact that the Ricci tensor satisfies the differential Bianchi identity

Where  is the divergence operator respect to

is the divergence operator respect to  and

and  is the scalar curvature of

is the scalar curvature of  (the trace of the Ricci tensor). This says that if we define a 1-form

(the trace of the Ricci tensor). This says that if we define a 1-form  by

by  , then in order for

, then in order for  to satisfy

to satisfy  we must have

we must have

To write  in coordinates, we start with

in coordinates, we start with

From

(which is just the definition of  in coordinates) and from the expression in local coordinates of the symbols

in coordinates) and from the expression in local coordinates of the symbols  , we easily see that

, we easily see that

![Bian(r,g)_{k}=g^{ij}\left[\partial_{i}r_{jk}-\frac{1}{2}\partial_{k}r_{ij}-g^{ls}r_{ks}\left(\partial_{i}g_{js}-\frac{1}{2}\partial_{s}g_{ij}\right)\right]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=Bian%28r%2Cg%29_%7Bk%7D%3Dg%5E%7Bij%7D%5Cleft%5B%5Cpartial_%7Bi%7Dr_%7Bjk%7D-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D%5Cpartial_%7Bk%7Dr_%7Bij%7D-g%5E%7Bls%7Dr_%7Bks%7D%5Cleft%28%5Cpartial_%7Bi%7Dg_%7Bjs%7D-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D%5Cpartial_%7Bs%7Dg_%7Bij%7D%5Cright%29%5Cright%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=444444&s=0&c=20201002)

As discussed in Besse’s book, Dennis DeTurck came up with examples of symmetric tensors that cannot satisfy the Bianchi identity respect to any metric. One of his examples is the following

Consider in  a symmetric tensor of the form

a symmetric tensor of the form

The existence of a metric  such that

such that  implies as we saw before that

implies as we saw before that  . In particular, from our expression for

. In particular, from our expression for  we must have

we must have

![0= Bian(r,g)_{1}=g^{ij}\left[\partial_{i}r_{j1}-\frac{1}{2}\partial_{1}r_{ij}-g^{ls}r_{1s}\left(\partial_{i}g_{js}-\frac{1}{2}\partial_{s}g_{ij}\right)\right]=](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=0%3D+Bian%28r%2Cg%29_%7B1%7D%3Dg%5E%7Bij%7D%5Cleft%5B%5Cpartial_%7Bi%7Dr_%7Bj1%7D-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D%5Cpartial_%7B1%7Dr_%7Bij%7D-g%5E%7Bls%7Dr_%7B1s%7D%5Cleft%28%5Cpartial_%7Bi%7Dg_%7Bjs%7D-%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D%5Cpartial_%7Bs%7Dg_%7Bij%7D%5Cright%29%5Cright%5D%3D+&bg=ffffff&fg=444444&s=0&c=20201002)

This implies that on the hyperplane  , the metric

, the metric  must satisfy

must satisfy  which is impossible for a Riemannian metric. It follows that for any point

which is impossible for a Riemannian metric. It follows that for any point  in the hyperplane

in the hyperplane  the equation

the equation  has no solution near

has no solution near  . Notice that at these points the tensor

. Notice that at these points the tensor  is singular.

is singular.

In the next post we will interpret the existence of examples like the one we have just discussed as a consequence of the non-ellipticity of the system  .

.